SteveMcCabe.net...

...being the online presence of Steve McCabe himself

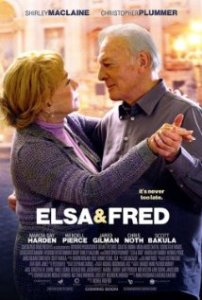

On Elsa & Fred, and why not all remakes need to be remade.

November 13th, 2014In 1996, Suo Masayuki made a quite delightful film called Shall We Dance? It was a deftly-crafted comedy of Japanese manners, and while it may ostensibly have been about Yakusho Kōji’s sarariman character learning to dance, it was in reality an exploration of Japanese social mores. In 2004, an American remake starred Richard Gere; this time, there was no exploration of anything, and the film was simply about a middle-aged bloke dancing with a younger woman. It entirely lacked the charm and the depth of the Japanese original; it was dull, it was crap.

I mention this by way of trying to figure out what went wrong with Elsa & Fred. The film is a remake of a Spanish-language Argentinian original that was clearly successful enough to convince Michael Radford to make an English-language version. I’ve not seen the original, but I’ll assume that it had depth and wit and character, just as Suo’s original of Shall We Dance? did. Certainly, Radford has done as good a job as Peter Chelsom did with Shall We Dance? in sucking any charm, any life, out of his American remake.

The setup is simple enough — Christopher Plummer and Shirley MacLaine, who both really ought to know much, much better, are the eponymous pair, living in adjacent flats in a building in New Orleans. He’s grumpy; she’s eccentric. Actually, she’s a pathological liar — or is she? (I offer this as an attempt to tease the story; after about half an hour you really won’t care.) They don’t hit it off the first time they meet. Guess how the story plays out — go on, just guess.

If you can’t figure out every single plot development, if you can’t predict how the story will work out almost from the beginning, then you’re simply not paying attention. MacLaine and Plummer do their best with woefully underwritten and under-developed characters; Plummer is the better of the two, finding more detail in the character of Fred than Radford and Anna Pavignano bothered to write into it, his accent wandering across the Atlantic almost at random and often straying into Patrick Stewart territory, while MacLaine simply dials the dotty up to eleven and delivers a performance with all the subtlety and complexity and sophistication of a Spinal Tap album. If you’re not going to invest any real time in a story, then fair enough. Not all films need a powerful story, if they have characters, or dialogue, or something, to underpin it — David Mamet’s almost perfect About Last Night is the standard reference text here. Elsa & Fred has none of this.

Much about this film is misjudged. The score is a series of aural signposts telling the audience what the director wants us to see: tinkling piano — look, she’s eccentric and crazy and zany; sweeping fiddles — look, they’re about to do something all madcap and fun and unexpectedly romantic. The supporting characters — Chris Noth is almost criminally wasted as Plummer’s son in law — are wheeled in and out to drive plot contrivances, not to do anything as interesting, or satisfying, as character development, something that is sorely lacking throughout the film.

There are moments when Radford appears to be trying to entertain and amuse — an attempt at a running gag at the expense of Fred’s late wife falls so flat as to be awkward. But for the most part Elsa & Fred simply plods along toward its inevitable, predictable ending. Along the way, however, it manages to exhibit some highly questionable racial politics. All the main characters are white — reasonable, I suppose, given that the majority of Americans are white. But there is a quite clear, quite obvious, caste system at work in the world of Elsa & Fred. Fred lives alone, so he has a home-help, Laverne. She’s black. She’s also a single mother whose daughter, mentioned in passing once, lives with Laverne’s sister in Pittsburgh. Armande, the super in Elsa and Fred’s building, is black. Shop assistants are black. When Elsa needs to go to hospital, the doctor is white, but just guess what race the nurse is — go on, just guess. It’s subtle at first, about the only thing in the film that is, but after a while there’s an inescapable apartheid at work. It felt wrong.

Racial issues notwithstanding, there’s nothing actively wrong with Elsa & Fred. It’s the kind of film you’d expect to see George Segal making with Glenda Jackson in the 1970s — indeed, Segal shows up as Fred’s best mate. But while the films that Segal was making forty years ago — A Touch of Class remains a high-water mark of the genre — were full of character and charm, Elsa & Fred falls flat. It wants to be a quirky, sharp, tart little comedy of manners. Instead, Radford has taken what was, we must assume, a very good Argentinian film, bled it dry of any actual human dimension, and instead delivered something quite devoid of joy, passion or any particular interest. Sad, really.

Leave a Reply