SteveMcCabe.net...

...being the online presence of Steve McCabe himself

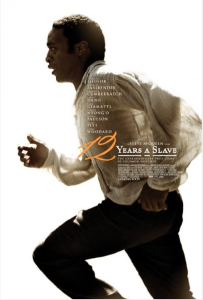

On 12 Years a Slave, and why cinema isn’t purely for entertainment

March 4th, 2014I finally saw 12 Years a Slave last night, the day after it won this year’s Best Picture Oscar — a well-deserved award. I had been wanting to see this film since I first heard of it, last year, but, rather than obtain a dodgy copy from a less-than-official Internet source, I waited until it came to my local cinema. A film like this rather needs to be seen in a cinema.

This is not, you will understand, a nice film. It’s not a happy film, hurried redemption at the end notwithstanding. It’s not even a terribly easy film, in many places, to watch. What it is is a quite brilliant telling of a story that is only made more heartbreaking by the fact that it is true. The story is one that’s been discussed at great and extensive length over the last few months — Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a free black northerner, is lured to Washington, in the slaver-friendly District of Columbia, where he is kidnapped and sold to a series of slave owners in the South. This, apparently, was far less uncommon than one might hope; what makes Northup’s story remarkable is that (and no, I really don’t think, at this stage, we can consider this to be a spoiler; even the title of the work hints at this) he manages to escape his captivity and, eventually, write his story.

The inexplicable atrocity that was American chattel slavery of the 1800s has been explored on screen before — it is customary, at this point, to mention Gone With The Wind, or Roots, and these two works do show the progression that exists in the way slavery has been depicted. Django Unchained tried to be the unflinching look that is still, however, overdue, but was simply too entertaining, and too much of a revenge-fantasy splatfest to be taken seriously as a commentary on the evils of slavery.

What 12 Years a Slave manages to do is show the daily mundanity of slavery. At the end of the day’s cotton-picking, each slave’s harvest is weighed out. The slave who has most displeased his owner, the slave who has picked least or who has, in some other way, managed to draw the wrong kind of attention to himself, or herself, is taken out and whipped. The power of 12 Years’ storytelling lies in the utterly matter-of-fact way that Epps the slaveowner, played with quite revoltingly psychopathic calmness by Michael Fassbender, sends each day’s victim to the whipping post, and the resignation with which the slave accepts that his life, his body, his being, is in the hands of a man who has bought him and owns him in entirety. The film does look away, slightly, from the treatment of female slaves. Epps owns Patsey (Lupito Nyong’o, earning herself a Best Supporting Actress Oscar in the process), and has the right to do with her as he will — she is, after all, her property. We are told, indirectly, that he uses her for sex, but the fact is addressed obliquely, cautiously, never addressing the fact that this was, simply, rape — a slave has no means of withholding consent, and so cannot be said to have given it. It was somewhat surprising that the film should have pulled this particular punch when it was quite willing to dwell on the savagery visited upon Solomon himself. A lynching scene that has Solomon barely able to survive lingers much longer than is even remotely comfortable for the viewer, and a flogging Epps delivers to Patsey is hard to watch.

Chiwetel Ejiofor was nominated for plenty of Best Actor awards, but I’m not totally sure he would have been the right choice. His character, make no mistake, suffered beyond understanding, but I’m really not convinced that Ejiofor truly captures him — his performance, while good, is a little one-dimensional, typically a thousand-yard stare. Altogether more interesting, both as a character and as a performance, was Sarah Paulson’s Mistress Epps, malevolent to the point of psychosis, goading her husband, calmly and dispassionately, to ever greater violence against Patsey. Benedict Cumberbatch was an odd casting choice as Ford, Solomon’s first, and marginally less evil, owner — as distinctive an appearance and voice as Cumberbatch’s only serve to take the audience out of the story, and you can’t help but think to yourself “Here, that’s Sherlock Holmes, that is;” a shame, then, because his is an entirely watchable and impressive performance. Similarly jarring is Brad Pitt as Bass, the abolitionist hired hand who helps Solomon to freedom — his oddly barking delivery sounds like a rehearsal for Inglorious Basterds’ Aldo Raines.

In the end, then, a film I’m glad I’ve seen. Not, necessarily, one I’ll want to see again — not for a while, at least; it’s simply too intense for repeated viewings — but one that should be seen.

Leave a Reply